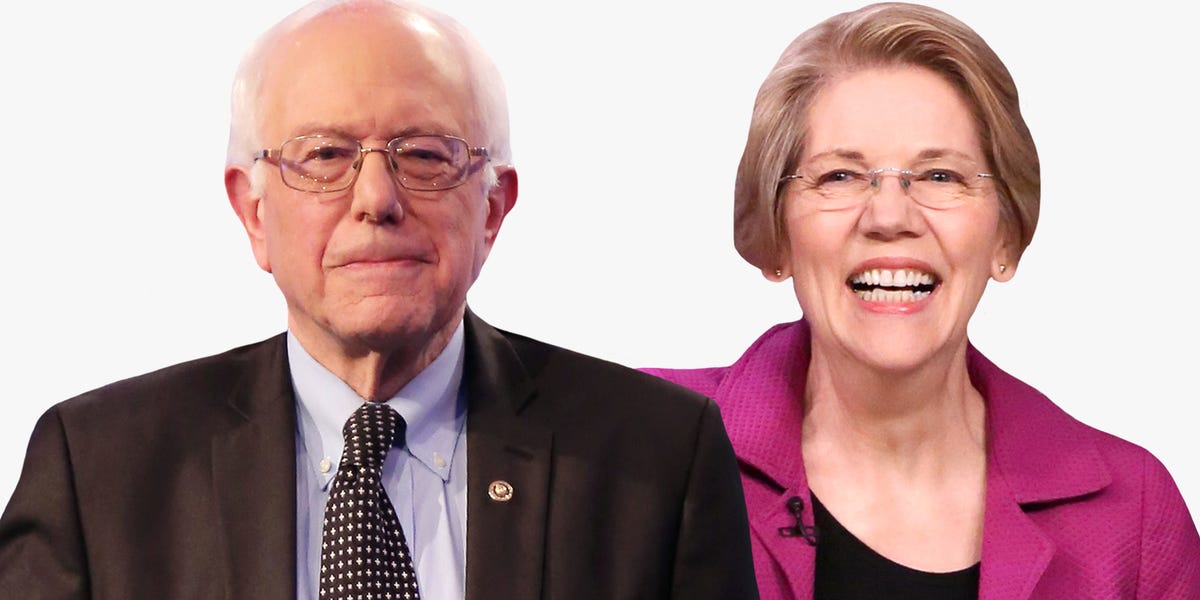

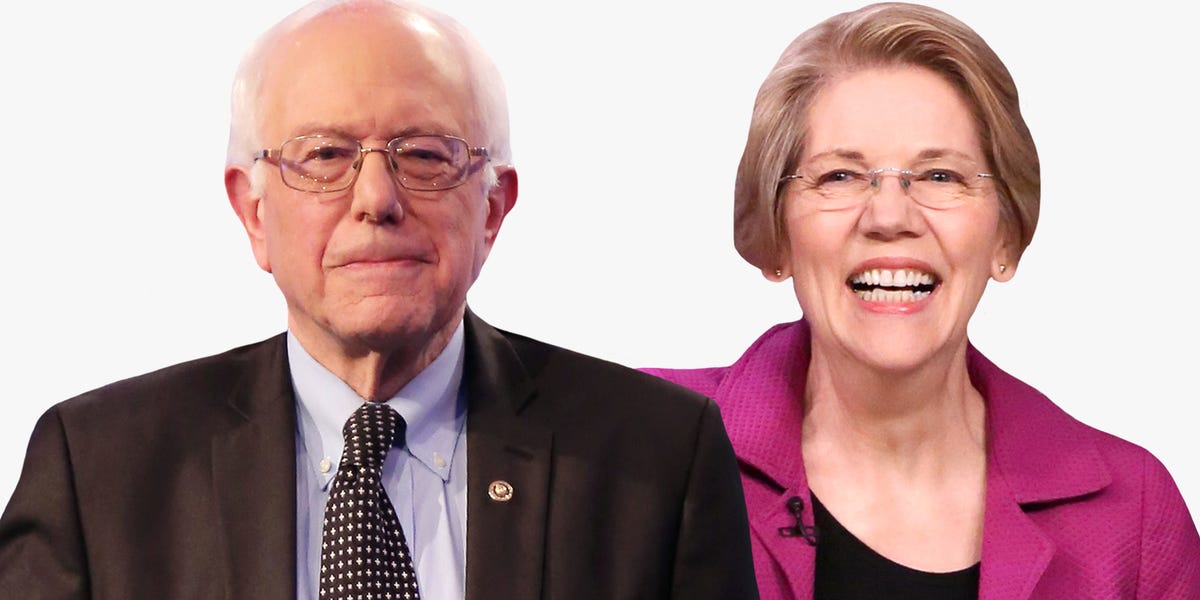

With so many contenders for the Democratic Party presidential nomination nearly two years out, it might be tempting to lump them into smaller categories to keep them all straight. Running in the furthest left lanes are Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT,) two figures both so closely associated with insurgent progressivism that observers often refer to the “Warren/Sanders wing of the Party.”

But if the two stand out among other Dem hopefuls for their shared eagerness to take on Wall Street, they somewhat splinter from there: Warren has taken especial care in recent months to emphasize that she’s a “capitalist to [her] bones”; Sanders is the nation’s most prominent self-avowed democratic socialist politician in decades. While they both place blame for the nation’s ills on the billionaire class, Warren’s political vision draws upon her background as a bankruptcy wonk and law professor to prioritize effective regulation to curb bad business behavior and write fairer rules for capitalism. Sanders’ perspective is shaped more by the mass movements of the 1960s on which he cut his teeth—he regards social problems as inherent to capitalism itself, striving to reallocate its spoils from one-percenters’ pockets into an expansive welfare state by building power from below.

Of course, there’s plenty of crossover there! And given the institutional constraints they’d be operating in, it’s tough to imagine any president—let alone a donor-irking lefty presiding over legislative and judicial branches still dominated by the Right – getting everything they want. Still, overarching ideology can dictate what a president prioritizes, how they use their bully pulpit, who winds up in their cabinet and what kind of down-ballot candidates gain traction.

Here’s a guide to thinking through the differences between Sanders and Warren, and what they might mean for their campaigns.

What’s the problem with Wall Street, anyway? Depends which candidate you ask.

Sanders and Warren are widely seen as the most credible Wall Street antagonists in the race—one Politico piece even reported that bankers would be satisfied with any president but those two. It’s quite the compliment, and the fact that Sanders and Warren are more interested in railing against the corporate class than in courting their donations puts them at odds with Democratic opponents like Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand and Kamala Harris, as well as third party hopeful and Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, who finds anti-billionaire rhetoric so distasteful he’d prefer people call them “people of means.”

Nonetheless, Warren and Sanders would likely stress different answers for why, exactly, Wall Street sucks. For Warren, it’s the cheating and the fraud, which allows the system to congeal into a form of “crony capitalism” that prevents it from working as intended. As a result, her regulatory solutions are usually aimed at making them work better: “so much of the work I’ve done,” she explained to The Atlantic, “are about making markets work for people, not making markets work for a handful of companies that scrape all the value off themselves. I believe in competition.” The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, which she formulated in the wake of the financial crisis, serves as a watchdog sniffing out the banking industry’s worst behavior and holding it accountable for breaking rules.

Sanders, meanwhile, would almost certainly agree that rampant fraud is a menace, but has a bit less love for capitalism “at its best” than Warren professes to. His recent town hall “CEOs vs. Workers” hints at his beef with the 1%—they got that rich by screwing over workers, forcing them to struggle to fulfill basic needs. No wonder his signature policy is taking megarich people’s money and funneling it into social democratic programs.

Which candidate is a stronger supporter of women?

In light of 2016’s shocking defeat of the first female major party candidate—and the forty-four male presidencies that preceded it—nominating a woman would be powerful, exciting and long overdue. And Warren has already made a case that the significance would be more than just symbolic—she’s already outlined a policy for universal affordable childcare, whose average monthly price rivals that of housing rents and which disproportionately burdens women. (It’s also worth noting that childcare and other family-centered policies, while central demands in most social democracies, aren’t always as prominently featured in Sanders’ sound bites as they should be.) Nonetheless, it’s also worth considering the feminist significance of the movement-oriented demands Sanders makes—single-payer healthcare liberates women from dependence on spouses and bosses, and relieves women from out of pocket healthcare costs exceeding those that men pay. Furthermore, Sanders’ support for the Fight for $15 campaign centers on minimum wage workers, who are disproportionately women of color.

Is it even possible to make either Sanders’ or Warren’s agendas come to life? ?

Let’s face it – from where we stand today, the agendas of Warren or Sanders feel rather far off. So of course it makes sense to wonder how, exactly, they’re planning on ramming it through the political system. At the moment, Democrats have a slim majority in the House but are outnumbered in the Senate. If the latter chamber flips control in 2020, the Democratic Party’s edge will be meager enough to be subject to the filibuster—a tactic of prolonging debate so as to intentionally spike a given bill, used increasingly frequently in recent years as a way to gum up the gears of government and neuter opposition. But in interviews, Warren has been more open to killing the norm than has Sanders, suggesting perhaps that a politician whose ideology hinges on well-designed rules knows that some are meant to be broken.

So what’s the take away?

It’s refreshing to have two major contenders on the Democratic side that are already making the uber rich shake in their ill-gotten boots. After all, when monied interests have too much power, they’re apt to push for things like tax cuts, shrunken safety nets, a hands-off approach to business regulation and a weakened labor force resigned to scraps. Of course, fully dismantling capitalism during the next presidential administration is an awfully tall order, and it’s unclear whether Sanders would even want to go that far if given the chance. Ultimately, if you’re a fan of “pre-distribution”—savvy regulations geared toward helping resources be spread around more fairly in the first place, vote Warren. If you prefer redistributing those resources with an eye toward more equitable outcomes, vote Sanders. For Warren, capitalism is a force for good as long as it’s working properly. For Sanders, it’s already working properly – and that’s the problem.

Be the first to comment