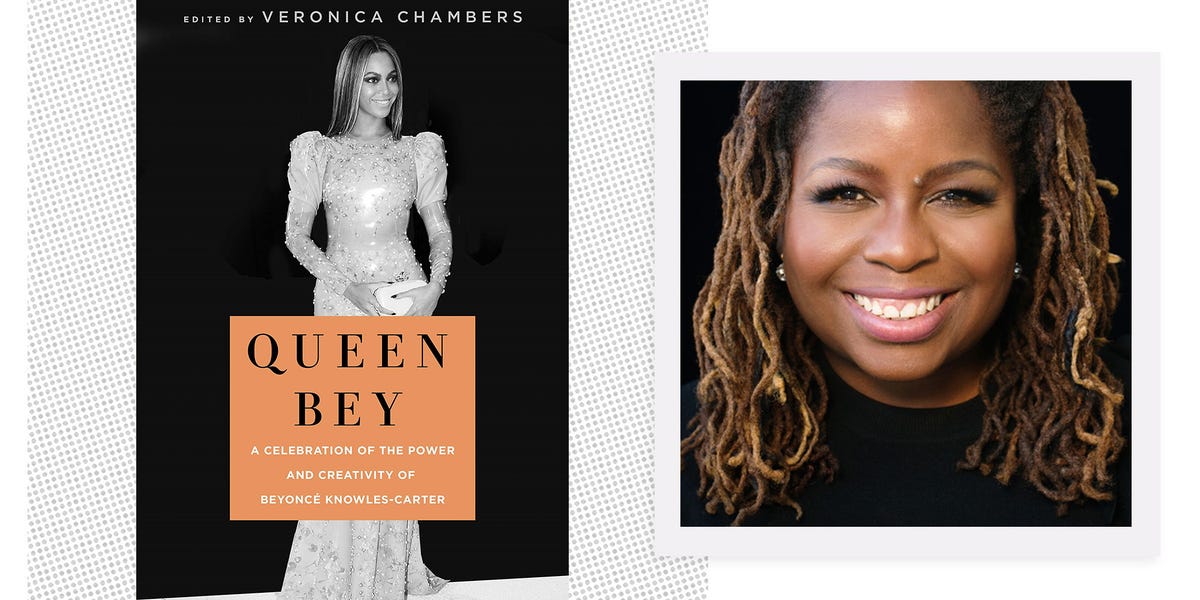

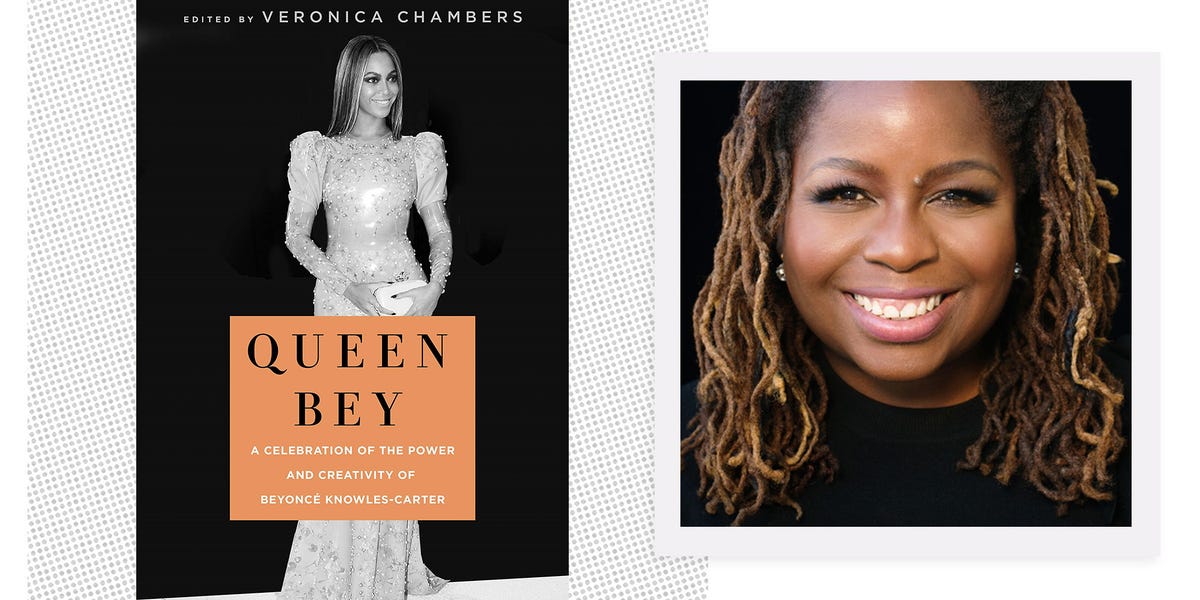

“Growing up as an Afro-Latina in America, in a country marked by constant reminders of race and racism, I have been asking and answering one question my whole life: What might a black girl be in this world?” So writes Veronica Chambers—author of the memoir Mama’s Girl, the New York Times bestseller Yes, Chef (with Marcus Samuelsson), and too many novels and other books to list here—in the opening pages of her new book, Queen Bey: A Celebration of the Power and Creativity of Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, a 22-author essay anthology out today (March 5) from St. Martin’s Press. “The incredible body of work that comprises the oeuvre of Beyoncé Knowles Carter seems to me an answer to that question too,” Chambers writes. “What might a black girl be in this world? Everything—and more than you ever imagined.”

Two years ago, Chambers’ anthology The Meaning of Michelle—16 writers celebrating the former first lady—hit bookshelves, e-readers, and the LA Times bestseller list. Having anthologized her longtime hero (“I was the ultimate Michelle Obama fan, just pure-out fan girl”) Chambers was ready to move on to someone she admired in a more “slow burn” sort of way; enter Beyoncé, the 37-year-old singer, dancer, actress, feminist, fashion icon, inspiration for the famous BeyHive, and, oh yeah, wife and mother of three; a woman who, in this diverse and comprehensive new collection, is called everything from “the veritable baddest chick in the game” (that’s Rutgers Professor and Eloquent Rage author Brittney Cooper), to “the planet’s most magnificent performer” (Georgetown Professor and author Michael Eric Dyson). Dyson compares Beyoncé to Michael Jackson—writing that she’s “snatched…the crown of best entertainer on the globe, ever.” With the release of her two “monumental visual albums, Beyoncé and Lemonade,” he writes, she has “revolutionize[d] the music industry.”

Chambers remembers first hearing Beyoncé in the late ’90s, when, struggling not long out of college to afford a New York City apartment, she heard the Destiny’s Child song Bills, Bills, Bills. “It had that chorus of ‘Can you pay my bills?’” she says. “And I was like, ‘I can pay my bills! I can’t do much else, but I can pay my bills.’ I loved that.” As time went on, she—like some of her contributors to Queen Bey—saw parallels between Beyoncé’s life and her own.

I connected with Chambers, a longtime colleague and contributor to my two anthologies, The Bitch in the House and The Bitch is Back, over margaritas and tapas in Manhattan’s Flatiron district, where we talked writers, writing, editing, power, sex and, of course, Bey, Jay, their 11-year marriage, and many of the other topics in this passionate book—including whether it’s harder to be a black man than a black woman in America, as some writers in Queen Bey take on, and what love really means.

Cathi Hanauer: You’ve edited two anthologies now and contributed to others. Clearly you like this multi-author, short essay format. It works beautifully here, because you have such a variety of perspectives—writers, professors, actors, influencers—all coming at different aspects of Beyoncé in different ways. It’s like a bunch of puzzle pieces that together create this beautiful whole; we not only see that whole, but having also seen the different pieces, we have a better understanding of it. Or should I say, her.

Veronica Chambers: I think a great anthology is like a great dinner party. [Queen Bey contributor] Ylonda Gault, for example, is like somebody sidling up to you at that party and saying, “By the way, my sister used to beat up people up for me, and she still will.” It’s not boring. It’s not, like, “So, what do you do for a living?”

CH: That’s part of what Gault writes about in your book: that her sister was her defender, just like Beyoncé’s sister, Solange, was Beyoncé’s. I love Gault’s essay; it’s funny, but also so moving. She talks about how she wasn’t a real Beyoncé fan until she saw the now famous elevator tape [of Solange going after Jay, who was rumored to be cheating on Beyoncé], but at that moment she fell in love with her, because she knew then that Beyoncé was real—”just as muddled, just as sure, just as hungry, just as wise, just as lacking…just as vulnerable as me.”

VC: Yes. We have many levels of celebrities showing us how real they are, but Beyoncé did something very different—and has continuously done it in a very different way. It’s not, like, “I was so tall and gangly and thin, I was the ugly duckling”—which can have that ring of, “My publicist told me to say it.” It was more like, “You’ve seen the elevator tape.” We know she’s dealt with some stuff.

CH: Contributor Maria Brito, an award-winning designer, author, and art curator, writes about running into Beyoncé at an exercise class in New York, when Brito was seven months pregnant, and how Beyoncé “looked at me and my belly with grace, surprise, delight, and a big, warm, Southern smile,”and then congratulated her. Hello awesome NYC celebrity encounter! It dawned on Brito that day that “Beyoncé’s artistry depends as much on her creativity as it does on her empathy, her vulnerability, and her humanity, all quintessential elements for being a true and lasting artist.” What do you think, if there is one, is Beyoncé’s message?

VC: The message evolves. I just constantly think of her as a blueprint for all the ways a woman can be. It’s proud, it’s creative…you know, when we did the subtitle for the book, we initially had, “Celebrating the beauty, power, and creativity of Beyoncé Knowles-Carter.” One day, my editor and I were looking at a mock-up of the cover, and we said, “We don’t really need to say she’s beautiful.” She is beautiful, she’s one of the most beautiful women we’ve ever known, but…I feel, especially over the last 5-to-8-years, that her work has really been about creativity and power.

CH: And love. Right? Contributor Meredith Broussard points out that “love” is the word that shows up most often in Beyoncé’s songs out of 500 words that showed up most frequently.

VC: But in using the word “love,” Beyoncé also shows us how complex it can be. It’s not like she’s talking about two little glass ornaments sitting on a shelf. It’s dirty love, it’s drunken love, it’s all kinds of love. And she does a really unique job of that, among her contemporaries.

CH: Lena Waithe says that in her essay. She’s an actor, producer, and screenwriter—you’ve got a lot of superstars! Waithe talks about how Beyoncé “gives you permission to stumble a little bit but then make something beautiful out of that stumble.” And about how, in her groundbreaking album Lemonade—in which Bey opened up about Jay-Z’s cheating, among other things—Beyoncé “talks about surviving heartbreak and betrayal,” and how there’s something “so human about it, and so brave.”

VC: I think that what Beyoncé and Jay-Z played out in public is probably happening in private for so many more celebrity couples than we can fathom. And his album [4:44, which followed Lemonade] was so interesting too. His interview with Dean Baquet, the executive editor of The New York Times, was such an interesting, man-to-man, high level conversation about not just what went down, but what all that meant to men trying to honor committed relationships.

CH: Speaking of men: Your contributor Brittney Cooper—who calls the Knowles-Carters “the First Couple of Hip-Hop, and only slightly less important to black folks under 35 than the Obamas”—also writes, movingly, about “the pain of a whole generation of black women who have had to love black men injured and traumatized by the ravages of Reaganomics, the prison industrial complex, and the war on drugs.” “Those social assaults on black men…change the otherwise loving nature of” these men, Cooper writes. Yet black women, she adds, have been pathologized as the cause of these problems. What do you think about this? Do you agree, as another contributor writes that black women have been taught, that life is easier for black women than for their male counterparts?

VC: The question of whether it’s harder to be a black man than a black woman is one I’ve wrestled with my whole life. Because I grew up with a little brother, who was always, to quote another famous black novel [by Alice Walker], “in love and in trouble.” And I felt like there was no space for me, because the worry was always that it was harder to be a black boy than a black girl. But when I was 15, and I slept on the streets because my home was so violent, I was afraid to stay there, every night I was in a lot of danger. At the end of the day, can you add that to all of the black boys who have been shot, and everything else? With full respect for the history of the danger black boys have been in in this country, the trauma and assault that black women face is really private and can kill you in an instant. Or it can kill you slowly in a thousand different ways. And I’m always concerned about the ways those women are not getting the care they need.

CH: Reflected no doubt in the high rates among black women of miscarriage, pre-term birth, stillbirth, and infant mortality. She has talked about her miscarriage before becoming pregnant with her daughter Blue Ivy, and how devastating that was. A similar theme in the book is that black love is hard. The baggage, the pressure of expectation. Beyoncé is married to a black man, and you to a white man. Do you want to speak to that at all?

VC: When my husband and I were first dating, he would say to me, when I was feeling insecure about a job I had, or something at work, “If you were half as arrogant as most of the white men I know, you would be ruling the world.” It was an up-close tutorial in the way this group navigates power. My husband’s not upper-class elite, he’s from a middle-class, nice Midwestern family. But still, everything I question, or have had questioned about me—what am I doing? how did I get here?—he’s like, “Don’t answer questions!” He says, “You know what a white guy does? He goes: ‘I’m fucking here.’”

CH: So, you’ve learned from him to be stronger? Or at least to try to seem stronger?

VC: Yes. But I’ve also sometimes missed having someone, during the hard days, who’s like, “Yeah, baby, it was hard for me, too.” That’s the thing I had to know, marrying him—that there was never going to be that moment where at the end of the day, we closed the door and slid down, our butts slumped to the floor, and said, “Wow, today was a hard day, being black in America.” We weren’t going to hold each other’s hand and have that conversation.

CH: Yeah. The solidarity of a soulmate—not to say that your husband isn’t one. Like Bey and J, and like all of us Marrieds, you and your own J—Jason—have been through some tough times, which I know because you wrote about it in The Bitch is Back! You’ve been married a long time too, now.

VC: Yes. And as someone who’s about to celebrate her 17th wedding anniversary, I think that the Carters’ Everything Is Love album, in 2018, was pretty special for me. That line “Can’t believe we made it.” I guess what echoes for me in Beyoncé is that I realize that things that were important to me, he didn’t necessarily know were important to me—but that on a day to day basis in my own marriage, I can see him adjust. And I think at the end of the day, all you can ask someone to do every day is adjust.

CH: I also think, with long-term marriage, that it comes down to, Do we want to stay together, or not? Both people have to want it. And if you both want to, you’ll work on it. Looking at it from the outside, it seems as if both Beyoncé and Jay-Z wanted that—to stay together. That’s why she stayed, after all the stuff that went down.

VC: And I want that for her, in this incredibly self-sacrificing way. There’s a whole generation of women who will walk down the aisle not believing in the fairy tale of marriage, and she gave us that! Why shouldn’t she have the grown-up, messy version of happily ever after, after doing such an amazing job creating all of these albums and exquisitely art-directed videos that showed us how hard it can be to have a grown-up relationship?

CH: What do you think it is about Beyoncé that makes her so unique? So special?

VC: [Contributor and acclaimed choreographer] Fatima Robinson talks about how rare it is, which I hadn’t really thought about, for someone to be at the same level as a performer, a vocalist, and a dancer. There are a lot of incredible vocalists, but someone who can do all three things at that level….

CH: True. And what else?

VC: Of all the gifts that Beyoncé was given—beauty, creativity, a lovely voice, all of it—she’s created something out of the parts that’s amplified by the hundreds by what she’s made of it. You know? We’ve had a lot of pretty things, a lot of vocal acrobats, but Beyoncé has made her name synonymous with an experience of music that’s only her own. Beyoncé is a work of art. A work of art of her own creation. She’s both the creator and the muse. [I think] We saw some of that with Joni Mitchell—there’s a famous quote by Graham Nash about that, that she was [like] the epitome of the singer-songwriter…and she was the muse, the California girl embodied. I think about that a lot with Bey—she’s both creating it and embodying it at the same time.

CH: You talked earlier about how you think that Beyoncé, like other black artists and creators today, owes a debt to Toni Morrison, because of the way Morrison layered her books. Am I getting that right?

VC: You see it in a Kendrick Lamar, in a Chance the Rapper, in a Beyoncé, a Chimamanda. There are things happening that you may get at first blush, if you have grown up black in America. And I think there are things you’ll get if you grew up rural, and things you’ll get if you studied art, or you read a lot of books. For me, Beyoncé’s instantly iconic Coachella set was a perfect example of that: You get the historically black colleges, the early Destiny’s Child, the art references. In her albums you get the huge exploration of marriage, but also sisterhood, and friendship…and she’s layering them really masterfully and purposefully.

CH: For anyone living under a rock, Beyoncé made history last spring by being the first woman of color to headline at the famous Coachella music festival—a performance that was called everything from “a cultural watershed moment” to “a gobsmacking marvel of choreography and musical direction,” and had that year’s festival renamed “Beychella.” In your book, Nigerian author Luvvie Ajayi sings its praises, not just because Beyoncé is “the greatest entertainer alive,” but also because “There is something really special about watching Bey in all her noir pixie dust, reminding folks over and over again that Blackness is something to be proud of.”

VC: Yes. When I was in college in the late ’80s and early ’90s, black work was still seen as outside the canon. But by the late ’90s/early 2000s, people like Toni Morrison were the American canon. So, it was no longer like, “Oh, you have to have read these white things to be well-read.” And what happens in a world where you can read, like, Toni Morrison and Chimamanda and Zadie Smith, and be incredibly well-read? You get a Beyoncé! Someone who is unapologetically black, and not forced to leave behind parts of her cultural self in a push towards integration in the ways that Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson were. Someone who is crossover without ever having had to cross over and leave some part of her behind. And I’m older than Beyoncé, but I think that’s part of my cultural heritage, too.

CH: I’ll leave it at that! Thank you so much for your wisdom and time.

VC: It was my pleasure. One of the joys of working so hard on this collection was knowing that on the other end, when the book came out, I’d get to spend months talking about Beyoncé!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Be the first to comment